Before starting I would like to provide some background assumptions. The success of the Fowler Landship during the Second Boer War (1899-1902) heightens military interest in "Mobile Forts" or "Landships". The British would continue to build and improve the Fowler Landship and probably also develop the more modest and less expensive "War Car". Due to expense there might be only a half dozen Fowler's in service until about 1910 or so and maybe a dozen models of a modified version of the Simm's War Car. These would reside in England and be shipped to Imperial trouble spots as required.

After 1910 other imperial nations would have begun their own armoured vehicle projects, notably the Austrians and Germans with the Burstyn MotorGeschutz/Kampfpanzer and Austro-Daimler armoured car.

The French and Russians would have the Charron Armoured Car, designed by the Russian M.A. Nakasjidze, based on his experiences from the then on-going Russo-Japanese war.

In Britain, the new tank would be steam powered, like the well-proven Fowler, and would probably resemble the rhomboid hull of WWI Entente tanks. I have named this the Heavy MK I(S) to differentiate from the I.C.E. powered version. Both these and, by this time, the Fowler Landship's would be multi-fuel - able to use any solid or liquid combustible material to heat the boiler. The War Car would be replaced by a version of the Pierce-Arrow armoured lorry.

Opening Moves - 1914

At the outbreak of war in Aug 1914, the availability of AFV’s of all types would be limited and their impact on the initial actions of WWI would be minor. There would be a notable exception in the form of the BEF, though more from accident than design. Further, of the two designs at this point, the Landship and the Tank, the former is the more mechanically reliable but none of the heavies are suitable for anything but the breakthrough phase of military operations due to their low cross country speed. Those Tanks still operational could be used to assist in securing the flanks of the breakthrough point and would be very useful in the defensive role during the inevitable counter attack as, dug in, they would become instant fortifications. As shown in Belgium, the vehicle most able to exploit a breakthrough was already available – the Armoured Car. The effect of the Minerva and available British vehicles in disrupting German operations was out of all proportion to their numbers but, without modification, would be useful on the Western Front only for a short period of time due to the destruction of the terrain by sustained artillery barrage. Medium tanks could negotiate the terrain but even these “fast” tanks only achieved a speed of 13 km/h, roughly half the speed of the more heavily armoured WWII infantry tank.

At the battle of Mons, the BEF numbered 70,000 men and 300 artillery guns. Now they also would have 18 Rolls-Royce (RNAS), 40 Admiralty Pattern (RNAS), 20 Light Tank Mk A, 20 Medium Tank Mk B (57mm), 10 Heavy Tank Mk I (2x 57mm). The Mediums and Heavies would certainly not be available at Mons and the BEF would still have to withdraw since the French 5th Army had done so. However, the presence of the AC’s and LT’s would cut British losses at the subsequent battle of Le Chateau in half, to about 4000, while increasing German losses. At both battles, the light tanks could stiffened the already formidable British line while the almost 50 armoured cars of the BEF would be able to constantly harass the flank of German 1st Army and even raid into its rear against lines of supply and communications.

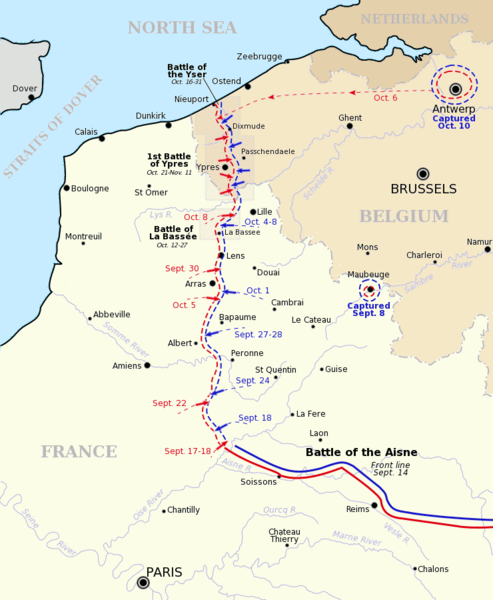

During the battle of the Marne the gap created by French 6th Army’s advance would be better exploited by the BEF, now with its full complement of armour. With it’s flank protected by French 5th Army, the British would be a very real threat to German 1st Army and might convince the German General Staff to begin the retreat of German forces sooner that 9 Sept. Taking into account the multiplication of force provided by British armour, it would be as if the 150,000 man German 1st Army were facing two armies of equal size. By keeping the pressure on 1st Army, the German right flank may have also been forced to retreat farther than the River Aisne and thereby affected the line of entrenchment created during the Race to the Sea, though fast armour would have to achieve the plateau via the Chemin des Dames south of the BEF.

By 10 Oct 1914 the BEF had been pulled back, reinforced, resupplied and repositioned to the north, near Ypres. During their subsequent advance, they ran headlong into the concentration of German troops preparing to attack towards Ypres. With every piece of British armour available assigned to the BEF, about 60 tanks and a similar number of armoured cars, they would have been able to do more than just hold the line and would have undoubtedly been able to push the Germans back during the battles of La Bassee and Ypres. The differences achieved would really be a matter of degree – the BEF would have suffered fewer losses, the Germans would suffer more casualties and would be driven back a little father or not be able to advance quite as far as in the historical record. The combined affect of each battle involving the BEF would place this part of the Western Front on a line from Neuport to Dismude (held by the Belgique) then to Passchendale, Lille, Lens, (held by the BEF) and Vimy, Bapdume, Peronne, Hom, Noyon, Soissons (held by French 6th Army) and on to the Swiss boarder with little change. A best case senario could see the trench lines meet the North Sea at Ostend rather than Newport and then extend southward to Lille but the overall effect would not be great.

On the Eastern Front the situation remained fluid but the Russians, though initially possessing a large army (115 infantry and 38 cavalry divisions with nearly 7,900 guns), continually suffered a deficiency in technical equipment due to its lack of heavy industry and depended greatly on war material imported from its allies. Historically, only by 1916 did build-up of Russian war industries increase production of war material and improve the supply situation. In all of 1914 Russia’s armoured resources consisted of 9 Russo-Balt S, 8 Packard (37mm auto-cannon) and 48 Austin I armoured cars and as many as 20 Kegress armoured halftracks based on the Russo-Balt M. Unfortunately, as previously noted, these would most likely be scattered across the entire front and would have little effect. Superior numbers on the Eastern Front had given the Russian army the advantage in the fall of 1914 allowing them to hold back renewed German assaults while advancing deeply against the Austrians in Galicia. Austrian armour would initially be restricted to a dozen Junovicz and Romfell armoured cars and a similar number of Burstyn tanks in Serbia, most of which isn’t good tank country. However, their presence would very likely prevent the complete destruction of Austrian 6th Army by the Serbian counter-attack on 3 Dec 1914, though General Potiorek would still order Austria-Hungary forces to retreat.

Analysis of 1914

By Aug 1914 the British would be the leading producer and user of armoured vehicles, with the dated Fowlers and Heavy Mk I(S) (which they might lend to Belgium in their time of need) and a number of the current Heavy Mk I, Medium B and the - now - Light A Whippet. These I see as being controlled by the Artillery, Infantry and Cavalry respectively, inter-service rivalry and politics being what they were. At this point there would be very little tactical effect by the presence of armour on the battlefield even for the BEF, which would possess some 90% of all existing armoured vehicles worldwide. The French and Italians would be late comers (as per historical inertia) but would work to catch up once they faced enemy armour or noted the British successes. In effect, French, Italian and American examples would be practically non-existent. I have estimated that at this time both the Germans and the Austrians have only one Armoured Cavalry Regt each and perhaps, if they consolidated all available armour, the Russians could be considered the have the same. If these forces operated as a unit it would be because of their specialized logistical requirements rather than any inclusive doctrine, a coincidence that could have good effect for the Austrians in Serbia as noted in the text. The German Armoured Cavalry Regt would probably have been employed in Belgium as part of the initial advance there and would have been available to somewhat counter the Belgique Minerva AC squadrons but would have run into difficulty facing even the obsolete Fowler and Heavy MkI(S), if these were in fact donated to Belgium by Britain. Still, though changes in events would have been a minor on a tactical level, on a strategic level the value of armour in combat would have been proven in late 1914 instead of late 1917. Furthermore, because of this, I believe greater attention would have been paid to the effectiveness of the armoured car in the traditional cavalry role of reconnaissance, flank protection and exploitation as shown by the RNAS and Belgium AC squadrons.

A Learning Experience - 1915

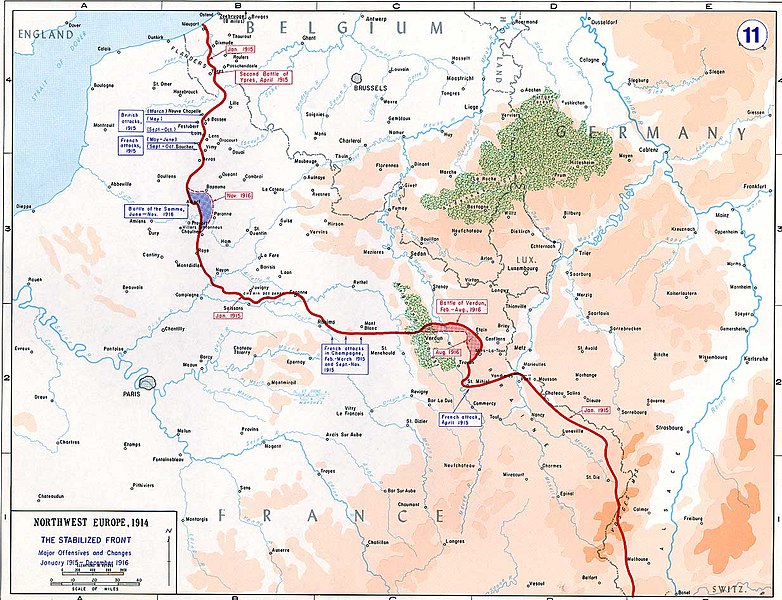

Joffre's plan of attack for 1915 was to attack the Noyon salient on both flanks in order to cut it off. The British would form the northern attack force by pressing eastward in Artois, while the French attacked in Champagne. In our altered timeline this salient still exists so the plan and subsequent action would remain much the same. The French portion of the northern attack would still be delayed a month and the southern attack would be just as unsuccessful. The British assault along a 2-mile (3 km) front by four divisions with tank support would be preceded by a concentrated bombardment lasting 35 minutes and make rapid progress toward Drocourt. However, the assault would still be slowed because of problems with logistics and communications that would allow the Germans to bring up reserves and counter-attack. Although the British advance would again be halted short of it's objective, the presence of armour on the battlefield would again reduce British losses possibly by as much as one-half, to around 5500 rather than 11,200. This would cause General French to come to the wrong conclusion, as in the historical record, except that he would assume a lack of both artillery and tanks to be the reason for lack of success. The German counter-attack at Second Ypres in April, 1915, would be a further blow, with many trained crews killed in the gas attack and many tanks lost to the enemy as part of the substantial losses of men and material inflicted on the Entente forces. In England these events would cause a change in government, with the recognition that the whole economy would have to be geared for war if the Allies were to prevail on the Western Front. In May the British would again press forward toward Drocourt, taking the town by May 25 with heavy losses. Although this would aid the French advance against Vimy Ridge, by preventing German reserve troops from being available to move there, Vimy would remain in German hands as per the historical record. The next Artois/Champagne Offensive would occur from Sept-Oct, 1915, resulting in devastating British, French and German losses for little or no territorial gains. Once again, it would be problems of logistics that would keep the British from exploiting the initial breakthrough and the presence of tanks and hard fighting on the part of the infantry that would keep them from being thrown back by the Germans.

In 1915 the German command decided to make its main effort on the Eastern Front, and accordingly transferred considerable forces there. Initially intended to relieve Russian pressure on the Austro-Hungarians to the south, the Gorlice-Tarnów Offensive lasted the majority of the campaigning season for 1915 resulting in the total collapse of the Russian lines and their retreat far into Russia. Trying to save Russian forces from suffering heavy casualties and gain time needed for the massive build-up of war industries at home, Russian Stavka decided to gradually evacuate Galicia and Polish salient to straighten out the frontline and started the strategic retreat that is known as a Great retreat of 1915. By the Sept 1915 Russia would have available 30 Garford I (76.2mm), 10 Russo-Balt T, 10 Russo-Balt D (37mm auto), 60 Austin II, 32 Lanchester, 30 Renault (37mm), 16 Peerless, 11 Ford, 4 Minerva (37mm auto) and 4 Pierce-Arrow (57mm) along with the first French produced V-II tanks. This would be countered by the Central powers production of the Romfell and Ehrhardt I armoured cars and the LK I, LK II (37mm), Motorgeschutz and Kampfpanzer I (37mm or 57mm). By Sept 1915 Germany would have 100 armoured vehicles on the Russian Front, including re-armed British tanks captured at Ypres, organized into 9 Sturmpanzerwagenabteilungen. Although too late for other operations of 1915 these may have played a part in the Sventiany Offensive, a military operation with limited objectives mostly undertaken by the 10th German Army against the 10th Russian Army from 8 Sept to 2 Oct, 1915. Historically, the effort failed due to a lack of infantry and artillery support and the intervention of Russian 2nd Army. Machinegun and artillery equipped armour would have made up for this and would have made it more difficult for 2nd Army to interfere, particularly with heavy tanks securing the flanks of the breach, forcing the Russians to commit their own armoured force of some 200 vehicles of various capability to the effort. Though only a tactical victory, the presence of these six cavalry divisions, with substantive armour support, to the rear of Russian 10th Army may have caused it to retreat further toward Minsk and created a German salient centred on that city before the breach could be closed. In our altered history, it would represent the first large-scale confrontation of armour vs armour.

In Serbia, events would unfold much as they had in the historical record. Even if the Austrians allocated every piece of surplus iron and steel in the empire to the production of tanks and armoured cars they still would not have provided sufficient armoured forces to have an overt effect on the outcome. Austrian third army may have been able to strike Serbian forces harder and advance deeper into Serbian territory, overwhelming the Montenegrin detachment acting as a covering force, but the best they could have achieved would be to cut off the northern most column retreating from Pristina somewhere in Montenegro. Although Serbia would fall in late 1915, and Montenegro in early 1916, surviving elements of the Serbian Army would take part in the fighting throughout the rest of the war on various fronts.

Analysis of 1915

By Christmas, 1914, the defensive lines on both sides of the Western Front would be well established and the Germans would have developed anti-tank tactics throughout 1915, in the form of tank traps, hedgehogs and direct fire artillery, just as they had developed other trench warfare tactics. Furthermore, with continual use and the changing combat environment, the British armoured force would by now be suffering from attrition through mechanical failure and battle losses. The wheeled armoured car, unable to operate unless the British adopt the Russian half-track concept, would be relegated to the Middle East and Russia. During 1915 the French and the Germans, now convinced by example of the value of armour, would both begin developing and building tanks and the British would begin to replenish and expand its supply of armour. Still, it would be nearly the end of 1915 before tank forces of any size had been gathered by the Germans, French and Russians and Austria would remain almost devoid of any armored vehicles, wheeled or tracked. Only the British would have armoured resources of any consequence in the form of Mk V Heavy tanks, heavy and medium tank-artillery and what ever remained of their medium and light tanks after a year and a half of fighting. For the most part, the presence of armoured vehicles would have little effect on the events of 1915.

The Bleeding of Nations - 1916

The Allied war strategy for 1916 was largely formulated during a conference at Chantilly, held between 6 December and 8 December 1915. It was decided that for the next year, simultaneous offensives would be mounted by the Russians in the East, the Italians (who had by now joined the Entente) in the Alps and the Anglo-French on the Western Front, thereby assailing the Central Powers from all sides. In January 1916 the decision was reached to mount a combined offensive where the French and British armies met astride the Somme River in Picardy. Plans for the joint offensive on the Somme had barely begun to take shape when the Germans launched the Battle of Verdun on 21 February 1916 and, as the Battle of Verdun dragged on, the aim of the Somme offensive changed from delivering a decisive blow against Germany, to relieving the pressure on the French army at Verdun. The Somme Offensive, fought from 1 July to 18 November 1916, would be among the largest battles of the First World War and one of the bloodiest military operations recorded. One purpose of the battle was to draw German forces away from the Battle of Verdun, which by its end would cause some 700,000 casualties with over 300,000 dead. It is at Verdun that French tanks would be deployed for the first time with disastrous results; 130 Schneider tanks and 93 St Chamond support battery’s destroyed out of the 365 vehicles employed.

The attack would be made by 13 British divisions (11 from the Fourth Army and two from the Third Army) north of the Somme River and 11 divisions of the French Sixth Army astride and south of the river. They were opposed by the German Second Army of General Fritz von Below in extensive trench lines and deep shellproof bunkers. In this altered timeline, the direction of attack would be toward Bapdume and Peronne, the apex of the two defensive lines that surrounded what had become the Arras Salient. The battle would be preceded by seven days of preliminary artillery bombardment, still largely ineffectual, so the subsequent attack would hardly be a surprise. Even with large numbers of Mark IV and V tanks and the troop carrying Mk V* the advancing British infantry would be doomed to suffer heavy losses. The presence of tanks would allow them to hold what was taken against German counter-attacks but the taking of it would still be costly. Of the 476 heavy and medium British tanks employed, 58% would be lost to mechanical failure or combat damage by November, with 65 destroyed and 90 captured by the enemy. Allied Casualties would remain above 600,000 though fatalities might be reduced to around 100,000 dead. German totals would remain much the same. The Germans would have been learning; beginning to move away from trench-based defences and towards a flexible defence in depth system of strongpoints that was difficult for the supporting artillery to suppress and close support artillery used in the anti-tank role, which would reduce the effectiveness of the tank in the advance.

In comparison, in the XXXV French Corps sector where the German defences would be relatively weak and the French artillery highly effective, the French divisions would have greater success. As per the historical record, the Germans, completely surprised by the French attack, would be completely overwhelmed. The French would advance without their new tanks, which were being systematically destroyed at Verdun. As tanks would allow British forces to hold prior to each advance, I expect that the final line would roughly follow the River Ancre to Bapaume and along the road to the Canal du Nord and the outskirts of Peronne. The cutting of the rail line and cross-roads at Bapaume would be of tactical significance but the town, like so many others would cease to exist. Once again, a failure of logistics and C3 would prevent an Entente breakthrough though many opportunities would be presented. Though less than successful, bordering on disastrous, the offensive had the strategic effect of causing the Germans to cease operations against Verdun and begin construction of fallback positions to shorten their defensive line.

Early in 1916 France called upon Russia to help relieve the pressure on Verdun by launching an offensive against the Germans on the Eastern Front, hoping Germany would transfer more units to the East to cope with the Russian attack. The Russians responded by initiating the disastrous Lake Naroch Offensive in the Vilna area where the Russians outnumber the opposing Germans by almost 5:1. However, due to poor artillery control and infantry tactics and well organized and fortified German defences, the whole operation was an utter failure that brought about the total lose of the entire Russian force without providing any help to the French. Because of the two day long artillery bombardment, Russian armoured units would be unusable during this offensive and the final outcome would remain the same. In comparison the subsequent Brusilov Offensive of 1916 would be considered the worst crisis of World War I for Austria-Hungary and the Triple Entente's greatest victory. Brusilov amassed four armies totalling 40 infantry divisions and 15 cavalry divisions. He faced 39 Austrian infantry divisions and 10 cavalry divisions formed in a row of three defensive lines, although later German reinforcements were brought up. On June 4, the Russians opened the offensive with a massive, accurate, but brief artillery barrage against the Austro-Hungarian lines. The key point of this was the brevity and accuracy of the bombardment, which destroyed enemy artillery positions, strong points and forward trenches while denying the defenders time to consolidate and maintained the integrity of the battlefield. The success of the breakthrough was helped in large part by Brusilov's innovation of shock troops to attack weak points along the Austrian lines to effect a breakthrough which the main Russian Army could then exploit. The initial attack was successful and the Austro-Hungarian lines were broken, enabling three of Brusilov's four armies to advance on a wide front. As Russian Eighth Army appears to have been the focal point of operations it is possible that all available armour would be assigned here – creating a 16th (armoured) cavalry division – rather than scattered among the four armies. If this had been the case then the effectiveness of the Polish Legions in delaying the Russian advance during the Battle of Kostiuchnówka would have been reduced if not negated. It could be argued that this force of 6,500 infantry and 800 cavalry, outnumbered 3:1, was primarily responsible for maintaining the Austrian line long enough for German reinforcements to arrive and shore it up. Had this not been the case the tactical retreat of Central Powers armies in July might have been a strategic route in June. Of further note is the fact that the Russian advanced so quickly that when Lutzk was taken on June 8, the Austrian commander, Archduke Josef Ferdinand, barely managed to escape the city before the Russians entered.

By overwhelming the Polish Legions quickly and possibly capturing Austrian 4th Army’s command element, Russian 8th Army would undoubtedly been able to drive on and capture the city of Kowel thus destabilizing the entire Austrian line and cutting rail communications to the south. This would have had the effect of accelerating the advances of the remainder of Brusilov’s Army Group and allowed them to achieve their objectives quicker and 11th Army to achieve it’s objective of capturing Lemburg. Even though General Alexei Evert, commander of the Russian Western Army Group, would very likely continue to drag his feet his advance of 18 June, though poorly planned and executed, would also have been more successful. Though only capable of threatening Vilna, it should at least have allowed the capture of Boranovichi and the rail line to Kowel, thus placing the entire north-south line from Boranovich to Kolomed in Russian hands. With 4th Army routed there would be nothing to stop 8th Army until Linsingen's counterattack on 24 July to thwart a possible thrust toward Brest-Litovsk and flanking of his Army Group South. The offensive would still die down in late September due to exhaustion of troops and overextension of supply lines and end with Russian troops having to be transferred to help Romania, which had joined the Entente in August and was now facing attacks by Austro-Hungarian, Bulgarian, Ottoman and German forces on two fronts. By the middle of January 1917, though the Romanian Army still fought, about half of Romania was under German occupation and the Russians were forced to send many divisions to the border area to prevent an invasion of southern Russia.

Analysis of 1916

By the end of 1916 the problem is no longer a scarcity of armour, particularly for the British, but the lack of an integrating doctrine for their use. Tank and anti-tank tactics as well as the proper role for each type of armoured vehicle is being learned in combat by both the crews and their officers as are the necessary changes is C3 and logistics. Both the Brusilov offensive in the east and the British offensive in the west, as described, would show that use of armour in the breakthrough and exploitation role to be highly effective even when the mechanical uncertainties of the state of the art are taken into account. In fact, if the Germans had been able to employ their meager armoured resources in the north to exploit the failure of the Lake Naroch Offensive, its effect would have been as great there as it was for the Russians in the south

Evolution, Revolution and Rebellion - 1917

At the beginning of 1917, the British and French were still searching for a way to achieve a strategic breakthrough on the Western Front. The previous year had been marked by the costly failure of the British offensive along the Somme River, while the French had been unable to take the initiative due to intense German pressure at Verdun. Both confrontations consumed enormous quantities of resources while achieving virtually no strategic gains. In a surprise move, on 24 February 1917, the German army made a strategic scorched earth withdrawal from the Somme battlefield to the prepared fortifications of the Hindenburg Line, thereby shortening the front line they had to occupy. The total length of the front was reduced by 50 km (30 miles) and enabled the Germans to release 13 divisions for service in reserve. The objective of the Arras offensive would therefore be the elimination what had become the Arras Salient, which was bracketed by the two arms of the Hindinburg Line radiating northward from Queant.

The first major British assault of the Battle of Arras (9 April to 16 May, 1917), as part of the Nivelle Offensive, was directly east of Arras with British Third Army attacking north of the Arras—Cambrai road. At roughly the same time, in perhaps the most carefully crafted portion of the entire offensive, the Canadian Corps launched an assault on Vimy Ridge. The objective of the Canadian Corps was to take control of the German-held high ground along an escarpment at the northernmost end of the Arras Offensive, thus ensuring that the southern flank could advance without suffering German enfilade fire. Third army was thereby able to advance deep into enemy lines. South of the Arras—Cambrai road Fifth Army did not fair as well and, due to the extend of the tactical errors involved, even the presence of Fifth Army's complement of tanks would do little to change this result. Still, by the end of the offensive, the Germans would be pushed back to the Drocourt-Queant Switch Line and the Arras salient all but eliminated.

By the standards of the Western front, the gains of the first two days were nothing short of spectacular. A great deal of ground was gained for relatively few casualties and a number of strategically significant points were captured, notably Vimy Ridge. Additionally, the offensive succeeded in drawing German troops away from the French offensive in the Aisne sector. These initial successes can be attributed to a mixture of technical and tactical innovation, meticulous planning, powerful artillery support, and extensive training, as well as the failure of the German Sixth Army to properly apply the German defensive doctrine. Despite significant early gains, they were unable to affect a breakthrough and the situation reverted to stalemate but the British learned important lessons about the need for close liaison between tanks, infantry, and artillery, which they would later apply in the Battle of Cambrai. On the German side, Gen Falkenhausen was removed from the command of Sixth Army and Ludendorff immediately ordered training in war of movement tactics and manoeuvre for his counterattack divisions.

The Second Battle of the Aisne (16 April – 9 May 1917) was the main action of the French portion of the Nivelle Offensive conducted to drive the Germans entirely from the Chemin des Dames plateau. On 25 January 1915 German forces had succeeded in capturing what remained of the French positions on the plateau won by the BEF in 1914. The front line then remained static until March 1917, during which time German defenders had created a network of deep shelters in old underground stone quarries below the top of Chemin des Dames plateau. On 16 April 1917, after a week of diversionary attacks by the British at Arras, nineteen divisions of the French 5th and 6th armies attacked the German line along an 80 km stretch from Soissons to Reims. On the first day French and Senegalese infantry and some the new French R-16 and R-17 tanks progressed to the top of the ridge in spite of intense German artillery fire and poor weather conditions. However, as French infantry reached the plateau it was slowed down and then stopped by the intense fire of a very high number of the new German MG08/15 machine guns and anti-tank artillery. During the following 12 days of the battle, French losses continued to rise to 120,000 casualties and 150 tanks. On 3 May the French 2nd Division refused to follow its orders to attack and this mutiny soon spread and developed into a threat of complete disintegration of the French Army. Following a final, ineffective four-day assault, the Nivelle Offensive was abandoned in disarray on 9 May 1917. The French high casualty count, in so few days and with such minimal gains, was perceived at headquarters and by the French public as a disaster. On 16 May, Nivelle had to resign and was replaced by the considerably more cautious Pétain, who made no attempts to commit his forces to large-scale offensives.

The opening phase of the Battle of Passchendaele began on 7 June 1917 when the British Second Army launched an offensive near the village of Mesen (Messines) in West Flanders, Belgium. Meticulously planned, and well executed, the assault secured a ridge running north from Messines village past Wytschaete village, which created a natural stronghold southeast of Ypres, overlooking the Ypres Salient. Close cooperation between infantry, artillery and tanks allowed for almost complete surprise and rapid advances. Had the British been prepared, they could have pushed forward immediately but the main assault would not being until 11 July, giving the Germans a month to prepare.

Apart from the 'ridges' the battlefield was very low-lying, almost no higher than sea level, and heavy spring rain combined with several years of fighting in the area had turned the naturally swampy terrain into an obstacle that even tanks could not navigate. In view of the failure of the British Fifth Army to make any appreciable headway, having advanced no farther than the village of Langemarck by 18 Aug, the main offensive was switched to British Second Army, which was to advance towards the southeast along the southern half of Passchendaele Ridge. With 1,295 guns concentrated in the area and the tanks allocated to 5th and 2nd army combined, essentially two armoured divisions, the attack was a major success and caused no small panic to German commanders. With the heavy tanks holding the flanks, the light and medium tank ranged across the ridgeline, advancing as far at the Flandern defensive line and, with infantry support, taking Polygon Wood and the town of Broodseinde by 25 Sept. A further advance had cleared the ridgeline by 3 Oct, breaching the Flandern line and liberating the towns of Passchendaele and Westrozebeke. The German forces within the Ypres Salient now faced the very real possibility of being surrounded and began a hurried withdrawal through the Poelkapelle Corridor. A large counter-attack at Broodseinde on 4 Oct failed to divide the British forces and sweep them from the ridge but a British attempt to advance to the Lye River on 9 Oct was no more successful. From 9-22 Oct, French 1st army and British 5th Army attempted to close off the Polkapelle Corridor but were too late to coral the fleeing Germans. The four divisions of the Canadian Corps were transferred to the Ypres Salient and tasked, along with the equivalent of one armoured division, with making additional advances northward toward Bruges from 26 Oct to 10 Nov. The assault position was directly south of the inter-army boundary between the British Fifth Army and Second Army. As a result the Canadian Corps was to attack with support of formations from the French First Army and British Fifth Army to the north and I Anzac Corps to the south. At the same time a Naval amphibious landing, Operation Hush, took place at Middelkerke on the coast despite a spoiling attack by German MarinesKorps in July. After 16 days of hard fighting the British had established a line from Middelkerke through Staden and Passchendaele to Lille. Though a huge gamble, the armoured assault along Passchendaele Ridge and the landings at Middelberke where stunning success, considered "the greatest victory since the Marne".

To the south, during the summer of 1917, a series of local attacks and counter-attacks were conducted by the French to gain control of high positions commanding the views between Craonne and Laffaux. Renault tanks were again used but this time their attack was coordinated with Assault Infantry and Engineers in S-17CA carriers and supported by StC-17BS close support artillery. By October, when troops from the 11th, 14th and 21st Army Corps attacked, the German defenders had been worn down and the victory at Malmaison forced the Germans to withdraw from the Chemin des Dames plateau and moved to the north of the Ailette river valley. This French victory did not compensate for the dramatic failure of the Nivelle Offensive, but it established a new strategy based on the massive use of modern equipment (artillery, tanks) concentrated on a specific point in the front. The British army would take over the defences at the western end of the line, from the plateau to the Ailette River, relieving the French, but henceforth the main burden of allied offensive efforts on the Western Front would fall upon British Empire forces and the soon-to-arrive American Expeditionary Force.

On 20 November, during the Battle of Cambrai, the British launched a massed tank against the strategically important town of Cambrai, which had become an important German railhead, billeting and headquarters town. This would be a test of the a new formation, the "Assault Division", combining tank, tank artillery and assault infantry that was being developed by the British. The operation was not designed as a breakthrough but as a coup de main to deny the enemy a key part of his communication and transport system. The battle opened with a surprise bombardment from 1000 guns followed by a creeping barrage and effective counter-battery fire. At this point, 350 tanks, 72 tank-artillery and 52 tank-carriers (each transporting a platoon of infantry or supplies) moved forward, crushing wire defences and suppressing firing from trenches and strong points. Fascines were dropped as makeshift bridges to enable the crossing of wide trenches by armoured vehicles while the tank-artillery of the 1st Tank-Artillery Regt provided direct and indirect suppressive fire on demand. The regular infantry from two British Corps then followed the tanks through the gaps they made, moving in “worms” rather than the familiar lines. The British advanced 8 kms on the first day at a cost of 65 tanks and 4000 casualties and would continue to advance, even as German reinforcements were brought against them, for as long as their tank formations remained viable. On 30 November, the Germans counter-attacked with 20 divisions, including storm-troopers, intending to cut of the neck of the salient and encircle the attacking British divisions. This included the first appearance of German tanks on the Western Front and by 3 December the British were forced to retire and dig in or face destruction. Though German defences had been easily breached on the first day, by 5 December the line had re-stabilized with Cambrai within sight and 179 British tanks captured or destroyed and most of the remainder out of commission.

In the east, by 1917, the Russian economy finally neared collapse under the strain of the war effort. While the equipment of the Russian armies actually improved due to the expansion of the war industry, the food shortages in the major urban centres brought about civil unrest that led to the abdication of the Tsar and the February Revolution. The very last offensive undertaken by the Russian Army in the war, the brief and unsuccessful Kerensky Offensive in July 1917, showed clearly that Russian army morale no longer existed and that no Russian general could now count on the soldiers under his command actually doing what they were ordered to do. Starting on July 1, 1917 Russian troops attacked the Austro-Hungarian and German forces in Galicia, pushing toward Lviv. The operations involved the Russian 11th, 7th and 8th Armies against the Austro-Hungarian/German South Army and the Austro-Hungarian 7th and 3rd Armies. Initial Russian success was the result of powerful bombardment, such as the enemy never witnessed before on the Russian front. The Austrians did not prove capable of resisting this bombardment and the broad gap in the enemy lines allowed Russians to advance without encountering any resistance. But demoralization of infantry soon began to tell, and the further successes were only due to the work of cavalry, artillery, large armoured formations and special "shock" battalions that general Kornilov had formed. The other troops, for the most part, refused to obey orders. The Russian advance collapsed altogether by July 16 and on July 18 the Germans and Austro-Hungarians counterattacked, meeting little resistance and pushing General Brusilov's forces back to their start line. Only the presence of every available piece of Russian armour, working closely with remaining elite cavalry, artillery and shock battalions, would keep the Russian lines from being broken. When the Germans attacked and captured Riga on September 1, 1917, the Russian soldiers defending the town refused to fight and fled from the advancing German troops. On November 29, 1917, the Communist Bolsheviks took power under their leader Vladimir Lenin and tried to end the war but the Germans demanded enormous concessions. When Russia withdrew from the negotiations in protest, the Central Powers repudiated the armistice on February 18, 1918, and in the next fortnight seized most of Ukraine, Belarus and the Baltic countries. As a German fleet approached the Gulf of Finland and Russia's capital Petrograd, on March 3 the Bolsheviks agreed to terms worse than those they had previously rejected and finally, in March 1918, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed and the Eastern Front ceased to be a war zone.

Analysis of 1917

It is in 1917 that everything begins to come together in the west. Armoured vehicles are being produced and are reaching the troops in sufficient numbers, tank design has evolved and combined arms tactics developed, and the strategic requirements of mechanized warfare are coming to be understood. Armour is now being deployed as unit formations and their strength focused rather than dispersed. Training doctrine developed by Canadian and Australian commanders would by now be applied to familiarize troops with operations that would include close cooperation between armoured, infantry, artillery and even air force resources. All of this would culminate in the successful Battle of Cambrai on 20 November 1917, which would be led by a specially trained and equipped "Assault Division" and supported by regular formations of infantry and artillery trained to operate with and complement the attached armoured formations. Though strategically inconclusive both the Cambrai and Malmaison attacks proved the effectiveness of still-developing combined arms tactics and training as well as the necessity of improving the reliability of armoured vehicles and support of armoured formations for sustained operations.

End Game - 1918

Following the successful Allied attack and penetration of the German defences at Cambrai, Ludendorff and Hindenburg determined that the only opportunity for German victory now lay in a decisive attack along the western front during the spring of 1918. Ludendorff's strategy would be to launch a massive offensive against the British and Commonwealth designed to breakthrough the Allied lines and advance in a north-west direction to seize the Channel ports which supplied the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and drive the BEF into the sea. With Russia withdrawn from the war, 33 divisions were now released from Eastern Front for deployment to the west giving Germany an advantage of 192 divisions to the Allied 178 divisions. In Russia, the German army had developed stormtrooper units, with infantry trained in Hutier tactics and supported by fast tanks to infiltrate and bypass enemy front line units, leaving these strongpoints to be "mopped-up" by follow-up troops. The stormtroopers' tactic was to attack and disrupt enemy headquarters, artillery units and supply depots in the rear areas, as well as to occupy territory rapidly. The attack would combine the new storm troop tactics with ground attack aircraft, tanks, and a carefully planned artillery barrage that would include gas attacks. This was nothing less than a precursor to the 'Blitzkrieg' concept that would be so successful in World War II, lacking only a suitable number of tanks. In this timeline Germany has enough tanks for three complete armoured divisions (plus reserves), both captured and manufactured, but the Entente forces have not been idle in that regard either.

By the date of Operation Michael, March 21, 1918, the British will have organized "Assault Divisions" containing three battalions of assault infantry (heavy infantry with tank-carriers and 2x mobile infantry with half-tracks), 8 battalions of tanks (each containing Heavy, Medium and Light companies) and a regiment of tank-artillery containing three battalions (two Heavy and one Medium) under the control of each Army’s headquarters. However, as of 21 March, this redistribution of forces would be only partially completed with most of the vehicles of the AEF and many of the newer vehicles of the BEF still in transit at the beginning of the German offensive. For instance, only a single Assault Division (including the 1st Tank-Artillery Regt) would be in place and fully equiped with the remaining divisions still forming or in transit and yet to receive their new half-tracks, tank-carriers and tanks. At this time the French would have a similar arrangement with fewer units spread over its ten army’s, rather than the BEF’s five army’s, while the army-sized AEF would have had enough equipment to provide an Assault Division for each Corps by the end of 1918. In the end, the final distribution of resources would be more even.

The attack was launched against the British Fifth Army and the right wing of the British Third Army by German 2nd, 17th and 18th Armies supported by a Corp (Gruppe Gayl) from Seventh Army containing the bulk of German armour. British forces were quickly overwhelmed and after two days Fifth Army was in full retreat, forcing the right wing of Third Army to also retreat to avoid being outflanked. The German breakthrough had occurred just to the north of the boundary between the French and British armies and the uncoordinated Entente response was slow in forming. After three days of swift advances 17th Army was charged with 'rolling up' British forces northwards while 18th Army was to head south-west destroying French reinforcements en route and threaten the approaches to Paris. 2nd Army, supported by Gruppe Gayl, was to attack west along the Somme towards the vital railway and communications centre of Amiens.

By the forth day, German forces had advanced past Amiens toward Abbeville and the BEF headquarters had relocated to Montreuil. Paris was now coming under long-range artillery attack and Pétain was increasingly convinced that the British 5th Army was beaten and had real fears that the 'main' German offensive was about to be launched against French forces in Champagne. On 24 March he informed Haig that the French army was preparing to fall back towards Beauvais to protect Paris, which would create a massive gap between the British and French armies, and almost certainly force the British to retreat towards the channel ports, creating a situation very similar to that of 1940. However the German advance was beginning to falter, as the advancing infantry became exhausted, it became increasingly difficult to move artillery and supplies forward to support them and British defence began to stiffen with the arrive of fresh troops and British tanks.

At the Allied conference at Doullens on 26 March the French General Ferdinand Foch was first given overall command of the fighting on the Western Front and later made generalissimo of all Entente forces. It was agreed to hold the Germans east of Abbeville and an increasing amount of French soldiers would come to the aid of Gough’s Fifth Army, eventually taking over large parts of the front south of Amiens. A German attack on British 3rd Army on 28 March failed to dislodge the British from Arras and the final German attack toward Abbeville on 4 April, which marked the first use of tanks simultaneously by both sides in the war and the largest tank battle to date, also failed. The newly formed British Fourth Army had included the only complete Assault Division and elements of two others reinforced 3rd and 5th Army. Operation Michael ended with a salient formed from Compiegne on the Oise River northwest to the Somme River east of Abbeville and northeast past Douliens and Arras to Douai. Though the Germans had advanced over 40 miles they had not achieved any of their strategic objectives. The British suffered 177,739 casualties and the loss of 1,300 artillery pieces and 200 tanks

The next part of the Offensive, Operation Georgette, took place from 9 - 29 April 1918 with the objective of capturing Ypres. Michael had drawn British forces to defend Abbeville, leaving the rail route through Hazebrouck and the approaches to the Channel ports of Calais, Boulogne and Dunkirk vulnerable to a German success that could choke the British into defeat. The attack was similar in planning, execution and effects, although with smaller dimensions, to the earlier Operation Michael but without the significant presence of tanks on either side. Though again failing in its strategic intent the German attack was able to make significant gains, pushing the British, French and Portugese forces back to Ypres, Hazebrough and Neuve Chappelle before being contained. While Georgette ground to a halt, a new attack on French positions was planned to draw forces further away from the Channel and allow renewed German progress in the north with the strategic objective again of splitting the British and French forces and gaining victory before American forces could make their presence felt on the battlefield. The German attack, named Operation Blücher-Yorck, took place from May 27 to 6 June, between Soissons and Rheims against French 6th Army and four divisions of the British IX Corps. As the French defences here had not been developed in depth the Feuerwalze was very effective and the Allied front, with a few notable exceptions, collapsed and no local reserves were available to delay the Germans once the front had broken. Once again shock troops and tanks were in the forefront and by 3 June the Germans had advanced to the outskirts of Paris before slowing due to casualties, supply shortages, fatigue and lack of reserves, establishing a line from Clermont to Senlis to Meaux and east along the Marne River to Rheims. A British counter-attack at Clermont and French-American attacks at Meaux and Chateau-Thierry prevented the Germans from advancing farther.

The Germans regrouped and renewed their advance westward with Operation Gneisenau on 8 June intending to draw yet more Entente reserves south and to link with the German salient at Amiens. Though the German advance was impressive, despite fierce French and American resistance, a sudden French counter-attack at Chantilly on June 11 caught the Germans by surprise and halted their advance. Gneisenau was called off the following day. The final German attack began on 15 July when 23 German divisions of the German 17th and 18th Armies assaulted the British Fifth Army east of Amiens. Meanwhile, 17 divisions of the German Seventh Army aided by the Ninth Army attacked the French Sixth Army to the west of Meaux. These attacks threatened to cut off the BEF in the north while moving to capture Paris in the south. Although the German armoured force, split between the two attacks, may have been sufficient to achieve one or the other they could not achieve both. The northern advance was finally able to capture Abbeville with some elements advancing as far as the channel coast, isolating the British forces in the north for 24 hours before a counter-attack by Fourth Army, with it's large armoured force, recaptured the town and its vital bridges and reopened communication with the south. The long slender salient extending from east of Abbeville to the mouth of the Somme River had simply been unsustainable with the German forces available. In the south, the Germans had captured a bridgehead across the Marne four miles deep and nine miles wide despite a counter-attack by the US 3rd division and the intervention of 225 French bombers which dropped 44 tons of bombs on the makeshift bridges, advancing to within 24kms of Paris. However, French 10th Army, supported by British XXII Corps and 8500 American troops, stalled the advance on 17 July and on 18 July, 24 French divisions, joined by the 4 British divisions of XXII Corps, 8 US divisions and 350 tanks, attacked the recently formed German salient. 10th Army itself employed 216 S-17CA, 131 StC-BS and 220 Renault tanks in their attack centred on Chateau-Thierry. Though losing 110 tanks, 43 tank-artillery and 28 tank-carriers to enemy fire the French were entirely successful, with Tenth Army and Sixth Army advancing five miles on the first day with Fifth Army and Ninth Army launching additional attacks west of Rheims. The Germans ordered a local retreat from the Marne Salient on 20 July and were forced all the way back to the positions where they had started their Spring Offensives earlier in the year. The Entente counter-attack ended on 6 August. Though the Kaiserschlacht offensive had yielded large, in First World War terms, territorial gains for the Germans, the strategic objective of a quick victory was not achieved and the German armies were severely depleted, with over 688,000 casualties and 753 tanks, 69 tank-artillery and 7 tank-carriers destroyed or captured, exhausted and in exposed positions. The remaining territorial gains around Ypres and Amiens were in the form of salients that greatly increased the length of the line that would have to be defended when reinforcements gave the Entente the initiative.

With the German advances halted and German forces in the south retreating, the BEF recommenced preparations for the coming planned offensive, which had been interrupted by the earlier execution of the German offensive, by bringing the Assault Divisions of each of its Armies up to strength and moving forward supplies and reinforcements to replace the men and material expended in the recent fighting. As no further British tank-artillery would be forthcoming, heavy artillery was to be towed behind tank carriers to compensate while French StC-17BS and American Holt Gun Carriers were to stand in for Medium Gun Carriers, creating 1 heavy and 2 medium battalions per regiment. Furthermore, all remaining Mk-IV, Mk-V and Mk-V* tanks were transferred to French command and 150 medium tanks were transferred to the AEF in exchange for 500 of the newest Mk-VI* and 1250 of the Americans Renault tanks. The French followed a similar arraignment, though with extra light tanks replacing medium tanks, to be attached to existing infantry divisions of the 3rd, 6th and 10th (GAR) and 5th and 9th (GAC) Armies (with US 1st Army (AEF) on the right flank). In 5th Army, the Italian 2nd Corps (3rd and 8th divisions), battle hardened but depleted, became that army’s assault division with fewer tanks and medium artillery but twice the heavy artillery and, late in the year, it is 5th Army that will receive France’s newest tank, the S-18. There was also a difference in developing tank doctrine. The French believed that the tank supported the infantry and, though it also had a heavy, breakthrough element, spread its light tank companies throughout the divisions of the controlling army. The British, and subsequently the Americans, believed this to be true only during the breakthrough phase and that the situation was reversed during the manoeuvre phase. Considering the lack of fast carriers for the French, except in 5th Army, this was understandable as it had been shown in previous battles that tanks without infantry became vulnerable. German tank tactics had been to breakthrough enemy defences and advance as far as possible as quickly as possible, with supporting infantry following at their own pace - they would now have the opportunity to develop defensive tank tactics.

On 8 August the Hundred Days Offensive was launched in the north against the Amiens Salient by British Forth Army, British III Corps north of the river and the Australian Corps and Canadian Corps to the south, supported by over 600 tanks and 800 aircraft, and French First Army, with over 1100 aircraft and a British Light Tank battalion. Through careful preparations, the Allies achieved complete surprise and the attack, spearheaded by heavy elements of 4th Assault Division, broke through the German lines creating a gap 24 kilometres long south of the Somme. British light and medium tanks, supported by cavalry (with armoured cars) and mobile infantry (with armoured half-tracks), moved through the southern breach to attack German rear positions, sowing panic and confusion. There was less success north of the river, where the British III Corps had only a single tank battalion in support, but Entente forces still pushed forward 12 km, effectively engulfing five German divisions. The advance continued for three more days, with the Entente forces advancing an additional 19 kilometres, as the Germans rushed in reinforcements. On 10 August, there were signs that the Germans were pulling out of the salient but by 13 August the rapid British advance had outrun their supporting artillery and supply lines and all but 6 tanks had been disabled or destroyed. On 15 August 1918, Haig refused demands from Foch that he continue the Amiens offensive, even though the attack was faltering, and instead launched an offensive toward Albert by the British Third Army, with the United States II Corps attached, which opened on 21 August. This developed into an advance that pushed the German Second Army back over a 55 km front and on 26 August the British First Army widened the attack by another 12 kilometres. As artillery and munitions were brought forward, the British Fourth Army, now supported by the 5th Assault Division (of 5th Army which was still reforming), also resumed its offensive. The Australian Corps crossed the Somme River on the night of 31 August, breaking the German lines at Mont St Quentin and Péronne and dealing a strong blow to five German divisions, including the elite 2nd German Guard Division. By the morning of 2 September the Canadian Corps had seized control of the Drocourt-Quéant line (representing the west edge of the Hindenburg Line) and forced the Germans to withdraw behind the Canal du Nord. Here, as in the south, the Germans had been forced back to the Hindenburg Line, from which they had launched their offensive in the spring. A total of 344 tanks and tank-artillery and 500 artillery pieces were captured or destroyed during the fighting.

Foch now planned a great concentric attack on the German lines in France (the Grand Offensive), with the various axes of advance converging on Liege in Belgium. Before this main offensive was launched, the remaining German salients west and east of the line were crushed - Soissons to Rheims on 12 September and Epehy to Canal du Nord on 18 September. On September 26, the Americans began their strike towards Sedan in the south; British and Belgian divisions drove towards Ghent (Belgium) on the 27th, and then British and French armies attacked across northern France on the 28th. The main U.S. effort of the Meuse-Argonne offensive, shared by the U.S. forces with the French 4th Army, took place in the Verdun Sector, immediately north and northwest of the town of Verdun, between 26 September and 11 November 1918. The American forces consisted initially of fifteen divisions and the French forces next to them of 31 divisions. Eventually, 22 American divisions would participate in the battle at one time or another, representing two full field armies, but most of the heavy equipment (tanks, artillery, aircraft) was provided by the European Allies. For the Meuse-Argonne front alone, this represented 2,780 artillery pieces, 380 tanks and 840 planes. They were opposed during the battle by parts of 44 German Divisions from the German Fifth Army, who would initially have no tanks available until they received the new StuPz OS and KfPz II late in the month. The objective of the offensive was the capture of the railroad hub at Sedan, which would break the rail net supporting the German Army in France and Flanders. The American attack began at 5:30 a.m. on September 26 with mixed results and by the subsequent day, September 27, most of 1st Army had failed to make any gains. Fortified MG bunkers and field guns used in the anti-tank roll cost the attacking American troops dearly. On September 29, six extra German divisions were deployed to oppose the American attack and the 5th Guards, with it's supporting tank battalion, and 52nd Division counterattacked, shattering the US 35th Division. The Germans initially made significant gains but were finally repulsed by the 35th Division's engineers and machine gun battalion. Battery D, 129th Field Artillery, in support of the 35th division, engaged the German tanks at point blank range, destroying a number of them, holding the Germans at bay long enough for the Mk-VI* tanks of the 306th tank battalion to move forward. The German light and medium tanks were no match for the American Mk-VI*, with its turreted 75mm gun, and quickly retired the field. On 4 October, the Americans launched a series of costly frontal assaults that finally broke through the main German defences (the Kriemhilde Stellung of the Hindenburg Line) between 14-17 October. By October 31 the Americans had advanced fifteen kilometres and had finally cleared the Argonne Forest. On their left the French had withstood the change of German tactics in September more uniformly and had advanced thirty kilometres, reaching the River Aisne. The American forces reorganized into two armies, facing portions of 31 German divisions, and continued their advance with French and American forces capturing Sedan and its critical railroad hub on November 6. American losses were exacerbated by the inexperience of many of the troops and tactics used during the early phases of the operation and, combined, the AEF and French 4th army had lost 125,000 men, 104 (about 50%) their heavy tanks and 144 (just over 33%) of their medium and light tanks.

To avoid the risk of having extensive German reserves massed against a single Allied attack, the assault along an incomplete portion of the Canal du Nord and on the outskirts of Cambrai was undertaken as part of a number of closely sequenced Allied attacks at separate points along the Western Front, between 27 September and 1 October 1918. The British High Command had fully realised that any success against the formidable defences of the Hindenberg Line could only be achieved with the use of tanks. The Canal du Nord defensive system was the German's last major prepared defensive position opposite the British First Army. It was nevertheless a significant obstacle as the Germans had taken measures to incorporate the unfinished canal into their defensive system. On the British First Army front, the Canadian Corps would lead the attack, crossing the largely dry canal between Sains-lès-Marquion and Mœuvres. In the early morning of September 27, all four divisions attacked under total darkness, taking the German defenders by absolute surprise. By mid morning, all defenders had retreated or been captured and XVII, VI and IV Corps of British Third Army moved in support to immediately and quickly exploited the territorial gain. Because of Canal du Nord's capture, the final road to Cambrai was open. American forces were ordered to attack on 27 September, to finish clearing German forces from outposts in front of the line. As a result of the confusion created by this attack (with the Corp command being unsure of where the American troops were), the attack on 29 September had to be started without the customary (and highly effective) artillery support - this was to have a large negative effect on the initial operations of the battle. On 29 September, the Australian Corps attacked, this time with the addition of two American Divisions from the American II Corps, supported by tanks of the 4th and 5th tank brigades (including the new trained American 301st Heavy Tank Battalion). The British 46th Division then succeeded in crossing the St Quentin Canal (defended by fortified machine gun and field gun positions), widening the breach in the Beaurevoir Line. Continuing attacks from 3 October to 12 October resulted in a total break in the Hindenburg Line, including the capture of Cambrai, with manoeuvre elements and cavalry of four British armies pushing the German line back to the Selle River.

Attacking on September 28, the Army Group of Flanders (G.A.F.) (comprising 12 Belgian divisions, 10 British divisions (from the BEF's 2nd Army) and 6 French Divisions (from the French 6th Army)) under the command of King Albert I of Belgium quickly penetrated the German defensive lines, advancing so quickly that by October 2 the offensive had outrun its supply line and was forced to stop to consolidate and reorganize. Continuing the attack, the Dutch border had been reached by October 20. By the Armistice, the front line had been advanced by an average of 45 miles, and ran from Terneuzen, to Ghent, along the River Scheldt to Ath and from there to Saint-Ghislain, where the front line linked up with the BEF on the Somme. The battle of the Selle, 17-25 October 1918, saw the British force the Germans out of a new defensive line along the River Selle. Breaching the Hindinburg Line had been costly and the British had needed two weeks to reorganize and to bring up their heavy tanks and artillery to prepare for the attack the new position. On 17 October Rawlinson’s Fourth Army attacked on a ten-mile front south of Le Cateau, making slow progress. By the evening of 19 October the First Army had fought its way into a position where it could also take part in the attack and early on the morning of 20 October the First and Third Armies attacked north of Le Cateau. Early on 23 October Haig launched a night attack with all three of his British armies, the First, Second and Fourth. This time the British advanced six miles in two days. The Germans formed another new line between Valenciennes and the Sambre, but that line was penetrated on 4 November after which the speed of the Allied advance increased. The Germans were now in a fighting withdrawal that would have seen them across the Rhine River by the end of the year if not for the Armistice on 11 Nov 1918. As it was, under constant pressure of successive Entente attacks from the North, Centre and South, they were pushed back to the River Meuse in a line from the Dutch boarder to Stenay, then to Etain and on to the Swiss boarder. This final offensive had seen over a million Entente casualties and the loss of 123% of Entente tanks, with half that number being destroyed. The German Army received almost 786,000 casualties and the loss, destroyed or captured, of almost all of their tanks, guns and aircraft north of Etain.

Analysis of 1918

When looking at the list of available armour, it would seem that the Germans has sufficient forces to take on any one of the Allies singly but were at a distinct disadvantage as a whole. In fact, the BEF was to become the major armoured threat as it, by mid-1918, had allotted one specially trained and equipped Assault Division for each of its five Armies. In the north (GAR and GAC), the French would eventually designate five existing infantry divisions, equipped with armoured vehicles, as Assault Divisions while the AEF had a single Assault Division under the control of their GHQ. At the time of Operation Michael, the single available French Assault Division was assigned to 10th Army while the US division was, by default, a part of 1st Army as US 2nd Army was still forming.

In comparison, the Germans initially had three “Sturmpanzerdivisions” formed into a single Corp (Gruppe Gayl) for their drive to the Channel and so had a distinct local tactical superiority. At the time the British and French only had one complete Assault Division each to face them, plus what ever could be quickly transferred from the AEF. Had Gruppe Gayl remained intact the Germans could very likely have achieved the isolation of the BEF in the north. Success in ‘driving the British into the sea’ would be questionable as British armoured forces would be building up at the same time that those of the Germans were being depleted. A better option would be to then have Gruppe Gayl move on Paris in the hope of a quick victory before the British could regroup and counter-attack, which they were able to do by 16 July. This would have amounted to a body blow against the already teetering and demoralized French and may very well have knocked them out of the war by the end of April or May, 1918. As it was, the German forces were doomed once the British were able to regain the initiative as they had put everything into the attack and had little left in the way of reserves with which to defend. Once resources had been properly distributed to the Armies involved, a German loss became inevitable.

Aftermath – 1918-1923

As the Allied forces broke the German lines at great cost, Prince Maximilian of Baden was appointed as Chancellor of Germany in October in order to negotiate an armistice, but the German armies were in retreat when the German Revolution put a new government in power. An armistice was quickly signed, that stopped all fighting on the Western Front on Armistice Day (11 November 1918). The German Imperial Monarchy collapsed as Ludendorff's successor General Groener agreed, for fear of a revolution like that in Russia the previous year, to support the moderate Social Democratic Government under Friedrich Ebert rather than sustain the Hohenzollern Monarchy. After the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on June 28, 1919 officially ended the war though the United States and Republic of China both negotiated a separate peace with Germany, which were finalized in 1921.

As the "the War to end all war" finally came to an end, other wars broke out immediately. These included the Finnish Civil War (1918), The Estonian and Latvian Wars of Independence (1918-1920), the Ukrainian War of Independence (1917-1921), The Polish Territorial Wars (1918-1921), the Irish War of Independence (1919–1921), the Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922), the Hungarian-Czechoslovak War (1919), the Hungarian-Romanian War (1919), The Turkish War of Independence (1919-1923), the Turkish-Armenian War (1919), Armenian-Azerbaijani war (1918 - 1920), the Russian Civil War (1917–1923) and Allied Intervention in Russia (1918-1920).

After the First World War, the nation of Poland was revived grouping together the territories occupied by Germany, Russia and Austria during the First, Second, and Third Partition of Poland. The Polish army soon came into being formed, for the most part, from a nucleus of Polish units that had been organized in France during the Great War. When units of the new Polish Army were sent to France for training with the French Army, an interest in armoured vehicles naturally developed. One regiment of Renault FT tanks arrived in Poland in June 1919 and one of its battalions took part in the Russo-Polish War of 1919-20. This war took a quite different form from the former entrenched type of warfare, which had prevailed, on the Western Front during WW1. Poland dispatched mechanized forces, combining armoured cars with motorized infantry and, truck drawn artillery. These units acted much out of their time and more as mechanized units do today - often engaged as deep raiding parties. With a peace treaty Polish armoured forces were reorganized along French lines. While the armoured cars were given to the Cavalry, the tanks became part of the Infantry and were established into a tank regiment of three battalions.

Poland had more than 20 armoured cars, in different variants, all captured in 1919-20 during Polish-Soviet war. More than 10 Austins of all types were captured by Poland, including 2 Austin-Putilov-Kegresse. Other captured Soviet vehicles used in Polish service were the Fiat-Izorski, 2 White, 2 White-ustin, 2 Peerless, 3 Garford-Putilov, 1 Jeffery-Poplavko and 1 Ehrhardt M17 armored cars. Purchased by Poland were 19 Peugeot 1918 and 17 Ford Tfc armoured cars, 174 Renault FT-17 and, according to one disputed source, received 5 A7V tanks. There were no more than 10 A7V's that survived WWI and were captured, then scrapped, by the allies. It is possible, though no evidence exists to support it, that the Poles received these 'scrapped' vehicles, repaired them and used them. If they received these as part of the reparation process, it is equally possible that they would receive the remainder of the German captured armoured equipment in our altered history. Either way, during this period Poland was certainly a force to be reckoned with.

Historically, the Red Russians retained the majority of armoured cars and this would still be the case in an altered timeline as these vehicles were used for policing duties by the provisional government before it fell to the Bolsheviks. However, the tank force would remain in the Ukraine under the control of the Tsarist Commander-in-Chief Mikhail Alekseev and very likely become part of his “Volunteer Army”. If the Intervention Forces chose to maintain and even supplement this armour it would be very possible for the Ukraine to remain a separate state, not part of the Soviet Union, until WWII.

No comments:

Post a Comment